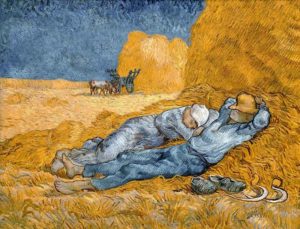

I say “nuclear”, you say “nucular”…

When I started writing this blog I didn’t imagine that my third post would be in defence of George W. Bush, but this has been a very surreal year…

Bush was mocked for mispronouncing the word “nuclear” as “nucular”, however, to be fair to him, he was far from the first person to do so – not even the first US president in fact (Dwight Eisenhower, Jimmy Carter and Bill Clinton had all made the same mistake). It is in fact an example of a very common aspect of language known as “metathesis”, from the Greek μετάθεσις meaning “put in a different order”, referring to the juxtaposition of sounds or syllables in a word.

Sometimes these mispronounced and misspelt words enter mainstream language. For example the word bird started life as brid in Old English. In Spanish, a recent attempt to have cocreta (a common metathesis of croqueta – croquette) officially recognised by the language’s Royal Academy narrowly failed.

Such mispronunciations become so engrained in how we speak, whether that be in our mother tongue or other languages we speak, that it becomes virtually impossible to say the word correctly, even if we know our version is incorrect. When speaking Spanish, I know the correct word for “crocodile” is cocodrilo, yet it always comes out as crocodilo, perhaps due to its similarity with its English equivalent. Curiously, the Spanish word is itself an example of metathesis (technically speaking non-adjacent metathesis) as it comes from the Latin root word crocodilus .

So perhaps I’m actually being more “authentic”!

There just remains one more thing to add – Happy Christmas!

Yo digo “nuclear”, tú dices “nucular”…

Cuando empecé a escribir este blog, no pude prever que la tercera entrada sería una apología de George W. Bush, pero ya ves, ha sido un año surrealista…

Se burlaron mucho de Bush por pronunciar mal “nuclear” como “nucular”. No obstante, en su defensa, no era ni de lejos la primera persona que lo hizo – ni incluso el primer presidente estadounidense (Dwight Eisenhower, Jimmy Carter and Bill Clinton ya habían caído en el mismo error). Es un ejemplo de un aspecto lingüístico muy común: “metátesis”, del griego μετάθεσις que significa “poner en otro orden”, que se refiere a la yuxtaposición de los sonidos o sílabas en una palabra.

A veces estas palabras mal pronunciadas y escritas llegan a formar parte del idioma “normal”. Por ejemplo, la palabra inglesa bird (“pájaro”) originalmente era brid en el inglés antiguo. En el castellano, hace poco había un intento para que la RAE reconociese cocreta como variante de croqueta pero no tuvo éxito.

Estos tropiezos llegan a ser tan profundamente arraigados en nuestro forma de hablar, sea nuestra lengua materna o una extranjera, que resulta virtualmente imposible pronunciar la palabra como tiene que ser, aun sabiendo que nuestra forma de decirla es incorrecta. Cuando hablo español, sé perfectamente que la palabra es cocodrilo, pero siempre me sale crocodilo, debido quizás a su similitud con crocodile en inglés. Resulta curioso descubrir que cocodrilo es en sí un ejemplo de metátesis (técnicamente se llama “metátesis no adyacente”) por venir de la raíz latina crocodilus .

Así que, a lo mejor, ¡yo soy el más “auténtico”!

Sólo hace falta añadir una cosa – ¡Feliz Navidad!